When I walked out of the bookstore onto Van Ness Avenue in San Francisco, I saw two of the Secret Service agents assigned to protect former President Jimmy Carter leaning close to one another, conferring. This was a decade ago, during Mr. Carter’s book tour for his memoir, “A Full Life.”

I’d worn my best black suit into the city, and the two Agents were wearing theirs, and so we three men in black observed the crowded line leading up to the store. One Agent turned slowly from the other — it was then I noticed the earpiece he wore, its coiled wire running from behind his ear then disappearing under his coat collar — and as he slowly turned his head, he counted off three locations with a trio of nods. One, as he noted the billboard atop the building at the corner of Turk Street; two, as he stared directly across Van Ness; and three, as his eyes lingered down that grand Avenue, toward the Beaux-Arts dome of San Francisco’s City Hall.

Either he was verifying that his snipers were in position, or perhaps he was simply focused on high vantage points across from the bookstore. Van Ness is six busy lanes of traffic. A lot of distractions there, plenty of noise from cars and buses jockeying for position. Maybe the best place for me was back inside — not out here where I could unintentionally be seen as impeding his effort to protect one of the former leaders of the free world and a Nobel Laureate.

Inside the store, bookcases had been pushed aside to provide space for the line of readers who had been queuing down the street for hours.

We booksellers gathered around the lead Secret Service agent after he left the busy street and listened while he explained what he expected of us.

“If someone’s just being loud,” he said, “we’ll let you take care of that.” And he looked over at his partner who was headed our way.

“Crowd control?” his partner addressed us. “That’s all you.” It took me a moment to realize he meant that we should politely ask any would-be hecklers to take their heckling outside. Ok, got it. Check. Though why someone would choose to heckle a 90-year-old statesman…

“If there’s any unexpected forward motion by someone,” he continued, “that’s not something for you to worry about.”

Ok, so the actual protection of the President would not be something we needed to concern ourselves with. Fair. They had the guns, we only had our books. Again, check.

He turned to leave, but I sidestepped and cut him off. I leaned in close, the same way his partner had, and quietly asked if he could let me know if Mr. Carter’s Code Name had changed from the time he was in office. I knew he had been referred to as Deacon then. Could he let me know if that had changed?

“No,” he said. He was polite, and while there may have been a hint of a smile, he was pretty definite about his answer. Still, he had smiled, so I asked one more question. “Is there any way you could deputize me for the day?” I said. “Maybe just give me my own Code-Name for the next few hours?” I was thinking something like Bestseller, or Cliffhanger, or even Cash — after all, I had put on my best black suit for the occasion.

“No,” he said. But his smile was bigger that time. Then he stepped back, waiting patiently to protect the President.

Undaunted, though without a Code Name of my own, I went and stood behind the stanchions we had positioned in the back of the store. When Mr. Carter’s aide arrived, in a red-flowered dress and flats, she let us know she’d like a few more people available to help move the line along. She looked at my coworker Elena and indicated she should be closer to where we had placed Mr. Carter’s chair. Then she looked my way, about to give me instructions, but she hesitated, looked confused.

“I’m a bookseller, too,” I said, and she laughed.

“Oh, sorry,” she said. “With your black suit I thought you were Secret Service.” She looked at the Agents close by.

I stood up a little straighter and didn’t mention that I didn’t get my own Code Name. I just took her instruction to stand to the left of where Mr. Carter would sit. And then there was some happy commotion as the man of the hour arrived. Jimmy Carter, in a crisply ironed striped shirt, hair as white as the cover of his book, and that famous Carter smile.

“Nice to meet you,” he said to us, “thank you for helping out.” Then he sat and the signing began with San Francisco’s Mayor Ed Lee first in line.

The rest of the event was successful and fast — so many people thrilled to meet a member of the most exclusive club in the world. He had that smile and a kind word for everyone. There was only one hiccup when a hippy-dippy woman decided she’d drop to the ground, crawl under the ropes and the table, all in order to hand a prayer shawl to Mr. Carter.

She was unsuccessful, made so by the two Agents who were picking her up before she had even made it to the ground. Those men were fast.

One attendee was actually a little grumpy at their actions. “This isn’t Russia,” he said to me. “Do you have to be so draconian?” Before I could answer — my good man, she was going to scurry under the table to get at the former President — he looked closer at my suit. “Do you all shop at the same store for those outfits?”

I decided to let him believe I was part of the Secret Service and just took his book with a smile and handed it to former president Jimmy Carter to sign.

* * *

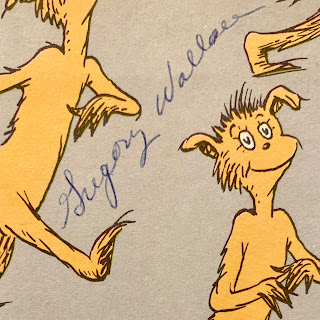

When the news was released shortly afterwards that President Carter had cancer, we were all surprised. It would have been easy to cancel his tour. Everyone would have understood. But he came, thrilling the hundreds of people who had lined up to meet him, shaking my hand when I offered it and thanking us all. Signing both his memoir for me along with my brag book — with a jaunty “Good job!” atop his signature.

All with a smile.

We laughed later, though, when the internet meme made its rounds, a photo of Mr. Carter with a saw in his hand, the words over the photo reading, “You may be Awesome, but you’ll never be 91-year-old Jimmy Carter building-homes-for-the-less-fortunate-while-fighting-cancer Awesome.

Has there been a President with a more esteemed period post-presidency? No. No, there hasn’t. He was always a gentleman. Respected as a person. Distinguished by his quiet grace. May his memory be eternal.